If you’re familiar with Slate Digital, there’s a very good chance the name Matthew Weiss rings several bells.

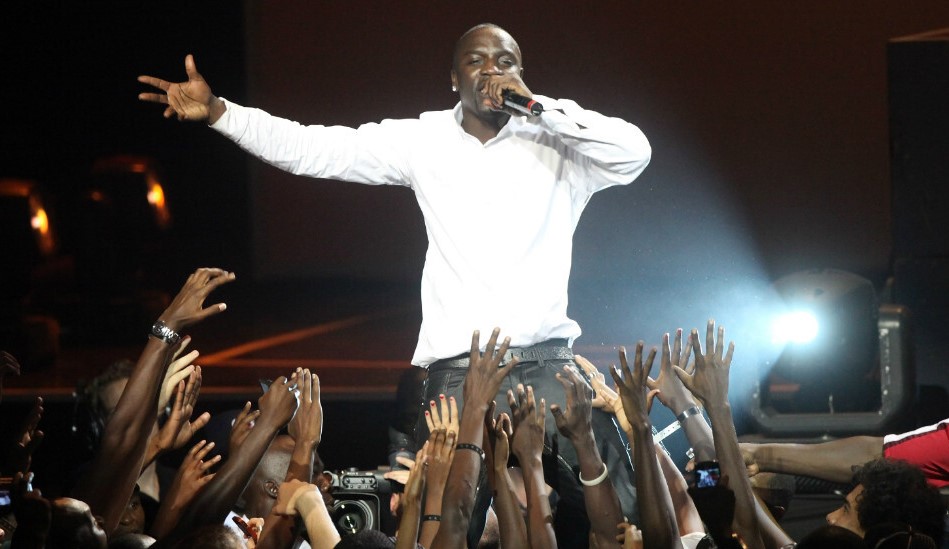

In addition to his pop mixing masterclass for our Slate Academy and a résumé boasting such names as Akon and Chris Brown, Matt recently launched Weiss Advice, a one-stop-shop for mixing and engineering guidance from an industry pro.

Matt was kind enough to sit down with us recently to answer some questions about his process and offer some insight into his general mixing philosophy.

Drew Van Buskirk: As a Philadelphia native, you know better than most that Philly is known for having a pretty signature sound. Were there any significant music movements taking place when you were getting started that kind of drove you in the direction of working in music professionally?

Matt Weiss: Oh yeah, for sure. My very first job as an in-house engineer was at a place called Studio E, which was run by a guy named Bobby Eli, who was a guitarist for MFSB, Gamble and Huff’s house band. He went on to be a producer for the whole Philadelphia movement, so I was getting a lot of Philly R&B clients right at the beginning. That’s where I started really forming my chops.

DV: At what point in that early development phase did it click for you that the studio was where you needed to be?

MW: When I was in college, during a summer break, I linked up with a rap group that I had been producing for and performing with. I had some conversations that sort of led me to ask myself, ‘Do I want to be on the artistic side, or do I want to be on the engineering side?’

I’ve said this before, but I’ll say it again because it’s a weird one—the conversation I had with KRS-One was probably the most like a light bulb moment. I asked him, ‘I’m kind of running these two paths. What would you do?’ He said, ‘The best way to stand in your light is to help somebody else stand in theirs.’

Well, I took that pretty literally, and decided that engineering was really what I was meant to be doing. That said, in a way I’ve been engineering since I was in middle school, so it was really always there. It was more a matter of acknowledging it.

DV: As you were developing your skill set in the studio, was there any skill that you found particularly hard to pin down?

MW: Being able to identify a good listening environment. You need to have a frame of reference in order to understand what good monitoring sounds like. If you’re used to lots of project studios and things like that, the idea of good monitoring is a little bit fuzzy. That one was probably the toughest.

DV: Do you have rules about what kind of rooms you like to work in that you’ve found apply in general to most spaces?

MW: You know, it’s so crazy—I’ve been in spaces that shouldn’t work on paper, and they sound amazing. My buddy Eric Racy’s mixing room, for example: if you looked at it, you’d be like, ‘This could not possibly work.’ And I swear to God, it’s one of the best sounding rooms I’ve ever mixed in. Then you go into rooms where, on paper, they look like they should work, and they do. Bob Horn’s room sounds fantastic. And then you go into rooms that look like they should work, they’re very fancy and everything…and the playback sounds terrible.

So, yes, there are general rules of thumb, but my experience has been that they kind of start going out the window when you put things into practical application.

I hope my non-answer is an answer.

DV: [laughs] It is. I want to talk a little bit about Weiss Advice, your latest venture into studio tutelage. It seems you’re focused on offering guidance, not solutions. You’re giving suggestions from learned experience. Is that deliberate?

MW: At Weiss Advice, the goal is to actually get people to become better at producing and mixing, and you can’t do that when there is an objective good or bad. Acknowledging that good and bad are subjective is really important.

I look at it this way—what’s a better getaway destination, Bermuda or Japan? There’s no answer to that. It just depends on what you want.

Ultimately, if you stick to absolutes, what you’re doing is trying to teach people how to be you. Time and time again, I see people say, ‘This is how you make this sound good.’ What they’re really saying is, ‘This is how I make this sound good.’ I’m not interested in doing that. I want people to sound like them to the best of their ability, because that’s what makes things interesting.

DV: In one of your recent videos, you made a point about being professional enough to acknowledge when something already sounds fine as it is. At the end of the day, producing is about executing the artist’s vision in a way that makes it the best that it can possibly be. That means context and nuance and feeling, not just the technical stuff.

MW: I’ve noticed that in forums and discussion boards, there’s an overarching focus on the negative. It’s really easy to focus on the negative, but I noticed that the real learning happens when you focus on the positive, especially in things that you don’t necessarily think should work. That’s what starts to show you that the things that do work are very subjective.

For example, people had a lot of opinions about the mix on Adele’s “Hello” when it first dropped. It’s like, wait a minute—this is one of the most successful songs in our modern day here. What’s happening in the mix? Yeah, the vocals are loud, but that’s because the vocals are the star of the show. I maybe would like to hear more of the piano, but the dark, rolled-off tone that’s there is to help present the emotion of a sadness or a longing. This kind of thinking is what led to my flagship course, “Mixing With Emotion.” Let’s stop focusing on how to EQ a piano and instead focus on what the listeners’ overall experience is going to be.

DV: Have there been any moments in recent studio memory where the performance or what was brought into the room was not where it needed to be, emotionally or technically?

MW: Well, because of COVID, the number of people I’ve been in the studio with has dropped significantly. The last three people that I worked with were Labrinth, André 3000 and Akon—some exceptionally talented artists. Most of the time I’m working with people who are really good and consistently give me 10 great takes to sift through.

At the end of the day, the heart of a performance is its emotional believability. A missed note or a flat note— that’s a problem of the past. If you listen to a take and you feel like it has something special to it, if you feel the magic and believe it, it’s worth whatever little edits you may need to make. The real key is to focus on the emotional side of a performance, not the technical.

DV: When it comes to a situation in the studio where you have to look at Akon and be like, ‘Okay, man, this is just not working,’ or, ‘We’ve got a lot of great ideas here, let’s hone in on one of them.’ Does that confidence come solely from practice and experience?

MW: Totally. I generally project a pretty confident image, but in reality, with Akon, he’s an A-Lister, and I was starting the relationship. At the start, my confidence on where to go with it and how much to direct him was a little shaky, but that dissipated after maybe six months. Akon is such a positive dude that he’ll make you believe you are the best person on Earth at whatever it is you are doing. If you just ordered a soda, he’d be like, ‘Yo, that’s the best soda here!’ And you’d be like, ‘Of course it is—I’m The Man at ordering soda!’

One of the most important things to remember is that, a lot of the time, interjecting doesn’t help. If you’re working with an artist who’s struggling and you’re trying to coach them along, one of the biggest mistakes I see people make is over-coaching. You’re supposed to be allowing the artist to feel like nobody’s watching their performance. It’s really important to make the artist comfortable.

DV: In terms of your general workflow, especially in the age of COVID, are you finding yourself working more in the box versus out, or is it case by case?

MW: In terms of my professional career, I started in 2007 on an API, that was my main desk. Then, I moved onto SSLs, because most studios had SSLs, but it wasn’t long before I was working mostly from a computer. In the very early days I would do maybe one or two tape sessions a year. By about 2014, none. I haven’t done a tape session in eight or nine years.

I try to stay in the box as much as possible, and not just because it’s smoother in terms of workflow. It also allows the mixing phase to be the secondary production phase it was always meant to be, a chance to extend the creativity that was laid down in the pre-production and production.

DV: Thinking about working in the box, is there any advice that you have for people who get a little intimidated by the tech talk and that’s why they don’t decide to take their journey a little bit further?

MW: I would say, you know, keep your set up fairly minimal. People sometimes ask me if I feel limited when I’m only using Slate stuff, and I say not even a little bit. I am barely limited when I’m only using stock plugins, so with the Slate series I feel like I have more than I need. You don’t need to have every piece of software or every piece of tech out there. Just go back to the musical ideas, the intention and the emotion of the new music. That’s the only thing that counts.

DV: You mentioned your recent work with Labrinth and André and Akon—is there anything else that you’ve been working on that’s got you jazzed?

MW: I’m really excited about what Reddick’s doing. I did a mix walkthrough of “I Am Detroit,” and I’m really happy with how that record came together. We’ve worked on a few records since, and I’m really proud of them. I think that they came together really well. I have really high hopes for this guy. He’s got the hustle, he’s got the drive, he’s got the talent.

DV: What have you been listening to that’s got you excited, outside of people that you’re working with?

MW: I just started listening to this Canadian R&B artist named Emanuel, who is fantastic. What an unbelievable talent. I gotta find his team and ask him if he needs an engineer at some point.

DV: Speaking of music we love, that reminds me. Growing up, like everyone else, I had certain genres of music that I really gravitated towards and others that just were not my thing. But I’ve noticed a recent trend where I’ll hear an up-and-coming producer or artist cite influences that are squarely focused in one genre or niche. Have you noticed this, too?

MW: I think it’s really important to keep in mind that genre is really variation within a form. The only way that you can create variation within that form is by diversifying, right? You can’t have variation if you’re doing the same thing. If you’re only listening to one artist or one genre of artists, all you’re doing is making a copy of something that’s already been done: you cannot be more successful than the original. Your palette needs to expand.

DV: That’s sound advice and feels like a perfect note to end on. Thank you for an awesome conversation.

MW: Absolutely! Have a good one.

For more production and mixing tips, visit weissadvice.com today!

Have a topic you’d like us to cover? Get in touch: suggestions@stevenslate.com